Tristram Fane Saunders works in London and lives inside his head. He has written five poetry chapbooks, most recently The Rake (the tale of an immortal dandy's past coming back to bite him) and Five Songs on a Cruel Instrument (which, for complicated reasons, he pretends was written by somebody else).

Tristram has performed his poems at festivals across the UK including Latitude and the Edinburgh Fringe, and appeared as a poetry critic on Radio 4's Front Row. In 2022 his poems have appeared in issues of The North, Poetry London, The Moth, and Oxford Poetry. He is also the editor of Edna St Vincent Millay: Poems and Satires.

Where do you write?

Usually when I’m not at home – parks are good, trains are better. When I’m writing at home, I might start sitting at my desk, but later end up sprawled on the floor or sofa, with my feet propped up slightly higher than my head.

Morning writer or late-night words?

Late-night.

Coffee, tea or any other drinks?

Coffee, tea, beer, gin, water, anything really.

Handwritten notes or phone files?

I usually write a draft by hand, then the next couple of drafts on a typewriter, and then make final edits on a crotchety 12-year-old laptop.

Something to nibble while you write?

I usually have some sort of snack on the go, but it can be anything. Otherwise, I’m chewing a pen.

What's your most tempting distraction?

The internet is my nemesis. Oh, the hours, the weeks I’ve wasted staring at Twitter.

Any desk essentials?

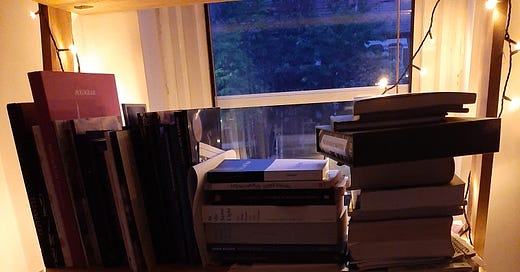

At the time of photographing my desk, objects on/below/above/behind it included: a map of the Shell Grotto in Margate; a curved letter-knife carved with the head of an unknown mammal; three cacti; three plantpots for those same cacti, including one shaped like an owl; a framed postcard of St Andrews Castle; a pack of Swan filters (not mine); a 1948 Remington Remette which makes a ringing sound like a struck wineglass each time I hit the letter I, O or P; four dozen books, mostly unread; a mousetrap; a stack of origami paper; an origami bird that looks like it evolved in a nuclear exclusion zone, one malformed wing far larger the other; a thank-you card; a pen; a coaster printed with the factually accurate, albeit ambiguous, slogan “There’s No Place Like Penge”; a landline phone; a printer; fairy lights; a very tiny clay bird. All these are, of course, essential.

What's on the speakers?

There are lots of lyricists who inspire me – Leonard Cohen, John Darnielle, Courtney Barnett – but if I’m writing I can’t listen to music with lyrics. Mainly ‘50s jazz pianists: Thelonious Monk, Bobby Timmons, Ahmad Jamal. Or if I want to feel dramatic, Anna Calvi.

What are your pre-writing rituals?

I can’t write unless I’ve spent an hour furiously not writing. A full 60 minutes of pacing the room, ripping up bits of paper, picking things up and putting them down again, losing my glasses, swearing under my breath, etc, etc.

Perfect bookshop to hide on a rainy day?

Topping and Co in St Andrews: you can sit beside a roaring fire, drink a pot of (free!) tea, and read the first hundred pages of a book before deciding whether or not to buy it.

The best word in the English language?

Open.

A poem that has changed your life:

If I’m honest, none of them. People have changed my life, but not poems. I wish I’d had a Rilkean “you must change your life” moment, but no poem has made me braver, kinder or taller. After reading thousands of the things – some of which I’ve loved – I’m still the same mess I’ve always been. The best poems, though, offer a brief escape from that mess. Jude Nutter’s Disco Jesus and the Wavering Virgins in Berlin, 2011 is a poem I’d like more people to read.